It's me, Celine. This is my last post. I will continue to tidy up and add to some of the skinnier posts on this blog through the next few days, but on the whole, this blog has served its purpose and can therefore be considered finished. If anyone is interested in continuing to follow along as I make my way through my final semester of graduate school, I will be updating on my train of thought every few days on my studio notes blog. Don't worry blog, it's not you, it's me.

Sunday, January 23, 2011

Last Days

Dear Blog,

Hi, it's me, Celine. My last day and a half in London was bittersweet. Wednesday I went to the Royal Academy of Art, followed by the Tate Modern to see the Gabriel Orozco show.

At the Royal Academy of Art I saw the "Aware: Art Fashion Identity" show, which I was initially hesitant to see, but turned out to be a good experience. I was hesitant because there are many shows that are basically fluff- shows arranged with little curatorial purpose other than to draw people into the museum. (Particularly when the image on the fliers for the show are so clearly meant to be sexy and seductive- see below). But I felt that it would be remiss of me to not see a show whose work is so closely related to the field of art jewelry. Although in academic discussions in the art world, fashion is rarely mentioned, this seems to me a major oversight-- after all, the way that most people experience jewelry is as an extension of fashion, and even the most academically-minded jeweler must admit that jewelry is meant to be worn on the body, and as such participates in many of the same discussions as fashion (a word that strangely connotes clothing, not sure why this is). The show covered an impressive (if somewhat schitzophrenic) range of what fashion could mean; alternately presenting runway garb, video art, performance work, theoretical clothing, and a four channel video exploring the garment industry in India. There were a few givens, such as Yoko Ono's "Cut Piece" and a large installation by Yinka Shonibare entitled "Rich Little Girls". There were also many artists who were included, I suspect, more for their name brand than for their reflection on fashion and identity (Acconci Studio's Umbruffla comes to mind, as does Cindy Sherman's Doll Clothes) This seemed an extension of a common theme; a field in its own right is only recognized as art when well known artists dabble in a craft with which they have little familiarity. Some of the most revelatory work was by artists whom I had never heard of, although this certainly does not mean that they have no following.

show whose work is so closely related to the field of art jewelry. Although in academic discussions in the art world, fashion is rarely mentioned, this seems to me a major oversight-- after all, the way that most people experience jewelry is as an extension of fashion, and even the most academically-minded jeweler must admit that jewelry is meant to be worn on the body, and as such participates in many of the same discussions as fashion (a word that strangely connotes clothing, not sure why this is). The show covered an impressive (if somewhat schitzophrenic) range of what fashion could mean; alternately presenting runway garb, video art, performance work, theoretical clothing, and a four channel video exploring the garment industry in India. There were a few givens, such as Yoko Ono's "Cut Piece" and a large installation by Yinka Shonibare entitled "Rich Little Girls". There were also many artists who were included, I suspect, more for their name brand than for their reflection on fashion and identity (Acconci Studio's Umbruffla comes to mind, as does Cindy Sherman's Doll Clothes) This seemed an extension of a common theme; a field in its own right is only recognized as art when well known artists dabble in a craft with which they have little familiarity. Some of the most revelatory work was by artists whom I had never heard of, although this certainly does not mean that they have no following.

Also at the Academy was Haunch of Venison, a solo show of French video artist Nicolas Provost's work. This was hands down one of my favorite shows in London.

It was raining hard when the Tate closed. Luckily I had my trusty umbrella. I walked across the Millenium bridge , past the steps of St. Paul's, and over to the ICA one last time to try and catch a lecture entitled "The Problem with Contemporary Sculpture". It was sold out. I can't imagine people lining up to pay to see a lecture on the state of contemporary sculpture here in the states. There wasn't even any standing room. After walking around a bit, I found a quiet pub near Trafalgar square, where I sat quietly in a corner, gathering my thoughts and munching on a traditional English meat pie. The waitress was very kind, and could tell that I was a tourist. I wonder what gave me away. Perhaps it was the map. After dinner, I met Iain near Nelson's Column. We walked to the Houses of Parliment, which looks its most imposing and majestic at night, when rows of warm orange spotlights illuminate the building from below, exaggerating its craggy gothic exterior. Iain's connections got us past the guards, down into the heart of the building, through numbers of long hallways and huge stone rooms that echoed like the walls of a cathedral, down into a cozy pub with green carpeting. I drank beer in the Houses of Parliment. It was great.

At the Royal Academy of Art I saw the "Aware: Art Fashion Identity" show, which I was initially hesitant to see, but turned out to be a good experience. I was hesitant because there are many shows that are basically fluff- shows arranged with little curatorial purpose other than to draw people into the museum. (Particularly when the image on the fliers for the show are so clearly meant to be sexy and seductive- see below). But I felt that it would be remiss of me to not see a

show whose work is so closely related to the field of art jewelry. Although in academic discussions in the art world, fashion is rarely mentioned, this seems to me a major oversight-- after all, the way that most people experience jewelry is as an extension of fashion, and even the most academically-minded jeweler must admit that jewelry is meant to be worn on the body, and as such participates in many of the same discussions as fashion (a word that strangely connotes clothing, not sure why this is). The show covered an impressive (if somewhat schitzophrenic) range of what fashion could mean; alternately presenting runway garb, video art, performance work, theoretical clothing, and a four channel video exploring the garment industry in India. There were a few givens, such as Yoko Ono's "Cut Piece" and a large installation by Yinka Shonibare entitled "Rich Little Girls". There were also many artists who were included, I suspect, more for their name brand than for their reflection on fashion and identity (Acconci Studio's Umbruffla comes to mind, as does Cindy Sherman's Doll Clothes) This seemed an extension of a common theme; a field in its own right is only recognized as art when well known artists dabble in a craft with which they have little familiarity. Some of the most revelatory work was by artists whom I had never heard of, although this certainly does not mean that they have no following.

show whose work is so closely related to the field of art jewelry. Although in academic discussions in the art world, fashion is rarely mentioned, this seems to me a major oversight-- after all, the way that most people experience jewelry is as an extension of fashion, and even the most academically-minded jeweler must admit that jewelry is meant to be worn on the body, and as such participates in many of the same discussions as fashion (a word that strangely connotes clothing, not sure why this is). The show covered an impressive (if somewhat schitzophrenic) range of what fashion could mean; alternately presenting runway garb, video art, performance work, theoretical clothing, and a four channel video exploring the garment industry in India. There were a few givens, such as Yoko Ono's "Cut Piece" and a large installation by Yinka Shonibare entitled "Rich Little Girls". There were also many artists who were included, I suspect, more for their name brand than for their reflection on fashion and identity (Acconci Studio's Umbruffla comes to mind, as does Cindy Sherman's Doll Clothes) This seemed an extension of a common theme; a field in its own right is only recognized as art when well known artists dabble in a craft with which they have little familiarity. Some of the most revelatory work was by artists whom I had never heard of, although this certainly does not mean that they have no following.Also at the Academy was Haunch of Venison, a solo show of French video artist Nicolas Provost's work. This was hands down one of my favorite shows in London.

It was raining hard when the Tate closed. Luckily I had my trusty umbrella. I walked across the Millenium bridge , past the steps of St. Paul's, and over to the ICA one last time to try and catch a lecture entitled "The Problem with Contemporary Sculpture". It was sold out. I can't imagine people lining up to pay to see a lecture on the state of contemporary sculpture here in the states. There wasn't even any standing room. After walking around a bit, I found a quiet pub near Trafalgar square, where I sat quietly in a corner, gathering my thoughts and munching on a traditional English meat pie. The waitress was very kind, and could tell that I was a tourist. I wonder what gave me away. Perhaps it was the map. After dinner, I met Iain near Nelson's Column. We walked to the Houses of Parliment, which looks its most imposing and majestic at night, when rows of warm orange spotlights illuminate the building from below, exaggerating its craggy gothic exterior. Iain's connections got us past the guards, down into the heart of the building, through numbers of long hallways and huge stone rooms that echoed like the walls of a cathedral, down into a cozy pub with green carpeting. I drank beer in the Houses of Parliment. It was great.

On my last day, I visited the British Museum once more to see the small drawing show, From Picasso to Mehretu, selections from the permanent collection. It was initially underwhelming, due in part to the size of the work; all were fairly small, and many were sketches or studies for larger pieces. It is also hard to compete with the sculptural work contained in the British Museum; some of the greatest works of mankind from the last 20,000 years is contained within that collection.

Wednesday, January 19, 2011

Unexpected

Dear Blog,

It's me, Celine. Yesterday was unexpected. I went to the same cafe yesterday morning that I've been going to almost every morning since I've been here. Then went to the Slade to have coffee with the director, Susan Collins, who knows my mother from Columbia. She was a lovely person, and had a lot of helpful things to say. Unfortunately, she's also a very busy person, so our interlude only lasted about half an hour. I then went to the Camden Arts Center, where there was a very interesting show up. The curator was former Turner prize winner Simon Starling (who I think I saw at an opening once, incidentally...) and some of the curatorial decisions were both unexpected and confusing, but overall a satisfying show (I will write much more about it later-- the ideas are still ruminating). I ended up staying there the entire afternoon, going through the exhibit, milling around in their fabulous bookstore, and having a large and protracted lunch while I watched the sun slowly set over a construction site. As I was leaving, a man came up to me and asked if I was going to another gallery- I answered that I didn't have one in mind. He said that he did, so we chatted and walked there together. It turns out he was an art student from South Hampton, returning to school to get his BFA after fifteen years. He was a pleasant, friendly man, and he ended up accompanying me to the ICA for a screening of the contemporary independent film Slakistan, a story of Pakistani twenty-somethings Islamabad, graduated from college and unsure what to do with their lives. Today, I'm going to try and find a pair of lace up boots in Oxford Circus. Also going to revisit the Saatchi gallery, the Tate Modern, the National Gallery, catch a lecture at the ICA on 'The Trouble with Contemporary Sculpture" and meet Iain for a drink at the Houses of Parliment (he works in the building, how cool is that?). It's going to be an epic day. We'll see how much of it I actually get through.

Tuesday, January 18, 2011

Update on whole hostel-situation-thing

Dear Blog,

It's me, Celine. The hostel I'm staying in is pretty bad. Leg-gnawingly bad. I have some small, humble understanding of what it must have been like living in a tenement. The best thing about the whole situation is that there are curtains around each tiny bed, which are stacked three high, in rows down the length of a 30' x 20' room. Imagine the stress, awkward glances, and fitful movements of a long and crowded public bus ride, extended to the length of an entire night.

I also forgot that I had put an old banana in my purse. I found said banana while walking home around midnight and thinking to myself 'i smell banana, why is that?' Consequently, I smelled rather funny the whole day. I'm sure the smell is still lurking in my purse, threatening to jump out at me if I have the gall to try and pay for something.

I saw Hamlet last night, in a standing room only performance at the National Theatre. I was standing. That didn't prevent it from being wonderful. It was, I realized, the first time I've ever seen Hamlet in its entirety. I've only seen a few clips of Hamlet from various sources (Kenneth Branaugh, Kirosawa, Frasier). I'm going to try and see King Lear tonight.

Monday, January 17, 2011

A Summupence.

Dear Blog,

It's me, Celine. The program is now officially over, as of one hour ago. The crew packed themselves onto a bus and I waddled away with my overstuffed luggage, down to a dingy hostel that smells of sweat and floor cleaner. I'm staying in a room with twenty other twenty-somethings, which will, hopefully, prove to be good fun. Or at least not result in me chewing off my own foot. There's standing room-only five pound tickets to Hamlet tonight, and I'm thinking of attending. It's fitting that I would be without a seat, as that, I think, is a good metaphor for where I stand (or don't stand) in things just now. Looking back on the last few weeks, I am surprised by the things that have clung to me. I think the best artwork grows in you slowly, building, changing and dislodging your thoughts inconspicuously, its vibrations resonating, building to a pitch until it is no longer possible to ignore. The best art acts upon the body like a tuning fork.

I have been returning time and again to a piece we saw on the second day here, in the Tate Modern. It was the residue of a site specific installation done in 2007 by Doris Salcedo, seen in the huge Turbine Hall where Ai Weiwei's Sunflower Seeds is currently installed. The work was/is entitled Shibboleth. The long chasm was meant to expose the racism upon which modernism and the contemporary Western world are built. For my purposes, it was more important that I saw the repair of the building; effectively the afterlife of the piece. A large concrete scar runs along the floor of the building, the lighter gray clearly visible against the darker, older concrete of the original floor. In her installation, Salcedo tore at the seams of the building, committing an act of violence against a seemingly impenetrable body. And to me, this idea of the body is key; for the building becomes a body through its destruction and repair. I have started to grapple more seriously than before with the notion that the body I am searching for exists already in the space upon which I choose to act.

It is strange and sad that this repair was not openly acknowledged as part of the piece, that the artist was not consulted in healing the wound she had unearthed- for I believe we are asked to consider that the artist here worked as an archaeologist, uncovering that which was already present.

High tea

Dear blog,

It's me, Celine. On Sunday, we had no fixed engagements other than convening for high tea at the National Gallery cafe. It was lovely to have tea and little finger sandwiches all together before our departure. More soon.

Gallery hopping on the East End

Dear Blog,

It's me, Celine. On Saturday we went gallery hopping on the East end. It was exhausting and good fun. Class in the evening, where everyone tried to sum up their experiences from the last two weeks and talk about what they would write their papers on upon their return.

Some highlights from gallery hopping are as follows.

Drawing Room

Small gallery located in a seemingly shady neighborhood. The gallery was behind a huge locked iron gate. The gallery assistant had to come down to open the gate. Once inside, the yard was dingy and sported a huge utility truck that looked as if it had been used to cart around artillery in the second world war. The gallery was on the third floor of a small warehouse building which was also the studio space for several artists. The interior of the gallery was modest, with high wood beamed ceilings and skylights. The show up was entitled Best Laid Plans and did not seem to be curated to any particular theme. There was a double channel video projection slideshow in the back showing advertisement stills and line drawings isolating the hand gestures shown in the ads. The artist is Katya Sander.

Friday, January 14, 2011

Thames River Cruise, Royal Observatory, Charles Dickens Pub, National Portrait Gallery

Dear Blog,

It's me, Celine. On Friday, we met at Westminster pier in the morning for the Thames river cruise. The boat dropped us off in Greenwich village, where Emily and I walked through the small market, had a lovely coffee in a fold-out espresso shop packed into the back of a tiny truck, and got lunch at a little corner restaurant. We then walked up to the Royal Observatory, where we spent the whole of the afternoon. I was struck by the intimate connection between time and place; we litened to a tour guide who told us of a famous 18th c English clockmaker, John Harrison, who invented the marine chronometer, the most reliable and precise clock to ever have been made at that time, that helped sailors in their navigation. It is fascinating that time could help people navigate through space. He ran into many problems because the change in humidity and temperature experienced during sea travel dramatically effected the mechanisms of clocks; also fascinating that something so entirely spacial could alter time (or rather our measurement of it). Harrison's solution to this problem was to use a bi-metal strip that would account for the swelling and shrinking of the pendulums.

In another room in the observatory, there was case after case of clocks, watches, and other time measurement devices (i.e. sundials). Eerily, all of the devices had stopped. Not one dial moved. It was as if time had died; the place felt a bit like a morgue. I felt as if I had entered into a chapter of Peter Pan.

From this room, I walked up a wrought iron spiral staircase to the main observatory; where the largest telescope (a 28" refracting telescope) is housed. The size of the telescope is quite impressive. A dramatic diagonal steel skeletal structure rises from the floor to the ceiling, holding the telescope in place. I heard what sounded like low bells ringing. It turns out the sound was actually an audio installation, Longplayer by Jem Finer. The following is a brief description of the piece from that wall text.

"<Longplayer is a> continuous musical composition written to play without repetition for 1,000 years. Music is created in real time from a 20 minute recording of Tibetan singing bowls. Every 2 minutes, 6 different exerpts are taken, modified in pitch, and then played back simultaneously by Super Collider Software. Finer describes Longplayer as growing out of a desire "to make something that made time as a long and slow process tangible." "

The piece contained unexpected cadences. It echoed, throbbed, pulsated; calling to itself accross the space. I sounded like the mournful bells of a clock. As I was listening, I could hear the beating of the rain against the roof. I was alone in the room. It was beautiful; the rain sounded like seconds ticking away. I became strangely more aware of my own internal movements; the pulsing of blood, throb of my heart, contraction of my muscles.

Around 5, we went to the Charles Dickens pub in Southwark. The pub was cozy and full of what looked like jolly locals. It was warm, and the local cask ale was the best we'd had yet. We ended the evening by going to the National Portrait gallery, which closes at 9 on Fridays.

Charles Dickens, Galleries, Evensong, Dutch Pancakes

Dear Blog,

On Thursday, we didn't have any fixed engagements. So I did a bit of writing in the morning, then wandered around the neighborhood a bit and gradually wound my way to the Charles Dickens museum. Went to a few galleries in the afternoon, and I ended up at Westminster Abbey for Evensong, the evening mass, at 5pm. I followed that up by reading for a bit in a cafe. Met Iain for dinner at a dutch pancake restaurant. Ended at a pub that was delightfully authentic until it was invaded by drunken American college students who high-fived the bar tender.

Wednesday, January 12, 2011

Tower of London, Whitechapel gallery, Brick Lane

Dear Blog,

It's me, Celine. On Wednesday we went to the Tower of London, then to the Whitechapel gallery. We finished with a late lunch on Brick Lane, known for its Indian and Bangladeshi food.

The Tower of London was not as bloody as I imagined. I had built up in my mind this idea that there would be blood still staining the walls from centuries of executions. This was not the case. Like many amazing buildings, its mazes of spiral staircases and precarious walkways had been cleaned, covered, stopped up, stunted and pruned to fit into the practical limitations of a tourist attraction. But like all such places, the imagination cannot help but roam the halls that are blocked, and the magic of a place with so much history is quickly internalized, to be digested at a later date. In many of the towers, there was centuries old graffiti covering the walls. The cream covered walls (possibly soapstone?) had initials, prayers, symbols of Jesus and the virgin, and in one case an imprisoned astrologer had carved a bas-relief of a globe on a rotating base. Some were, raw, hurried, while others were deep and had been carved in slow detail. Almost all the carvings were covered by clear plexiglass and bolted into the walls. It struck me as sad and slightly absurd that these desperate acts of remembrance were being cut off from the present and the future; they were being frozen- wouldn't it be wonderful to allow the building and the messages it contained to live on by allowing them to change? This is whimsical, to be sure. It was incredible to see those dimly and deeply scratched words from hundreds of years ago, and if people continued to leave their marks, in time the old would be erased. Which I suppose it will, anyways. The plexiglass simply delays the inevitable.

Francesca Woodman, British Museum, Class

Dear Blog,

Hi, it's me, Celine. On Tuesday we were supposed to go to the British Museum, then class. With a a museum induced agoraphobia quickly setting in, I cheated and went to the Victoria Miro gallery on the east end to see a show of Francesca Woodman's prints. I was really taken with her work. It seems swift and almost unplanned, as if the photographs are documentation of her responding to the work around her. In some images, she constrains the body, wrapping, pinching, confining it, while in others she fragments the body by using squares of glass to reflect light back at the camera, obscuring the body part being covered. She is constantly involved in a game of concealing and revealing, sometimes covering the body to blend in with the natural environment (I believe these were done at the same time as Ana Mendietta, but must look into this) and in several images leaving traces of the body in space.

Tuesday, January 11, 2011

V&A, Barbican

Hello Blog,

It’s me, Celine. On Monday we had a tour of the V&A with Glenn Adamson. Spent the day there, and ended it by going to the Barbican center to catch the Damien Ortega show. Stayed at the Barbican for the National Theatre of Scotland's performance of Black Watch.

To start with, I am creepily obsessed with Glenn Adamson's brain. Wanted to ask for his autograph or possibly something he has licked. He had some surprising things to say about craft- here are a couple of quotes.

"Post-disciplinarity is great as long as people remember they still need to know how to make things"

"Artists have complete responsibility of the manner in which their work is made"

Artist who outsource their work are "dealing in the medium of other people's hands"

After the tour, I lurked in the background like an over-caffeinated gollum waiting to pounce on him and ask more questions. Despite my creepy persistence he got away. I wanted to ask him how he felt about the use of the word 'handmade' in contemporary art (and actually, now that I think about it, the use of said word in advertising) and also what he thought about the idea that making is inherently political. This idea is being pushed hard by the DIY movement, and I am becoming increasingly jaded and cynical about the whole mess.

One of my favorite pieces in the V&A was Cornelia Parker's 2001 commission for the museum entitled Breathless. Parker has steamrolled the brass instruments, squeezing the breath from them as one squeezes toothpaste from a tube. The lifeless shells are then "pinned like butterflies" as Glenn put it, in the museum's collection- deflated of their former glory.

The V&A was completely overwhelming; felt like my brain was being put through a juicer. Spent a shameful amount of time thinking about finding a corner I could crawl into and take a nap. Finally found one on the fourth floor in the form of a movie theatre from the 20's playing relaxing ragtime. Thought better of it and decided to take my sickly, sniffy self in hand and go learn something. Ended up in the William Morris area. Noisy wallpaper. Very beautiful wife.

On the first floor was Shadow Catchers: Camera-less Photography, the featured exhibition. I was surprised by how much of the work seemed to have a spiritual bent to it: take the piece to the left (Floris Neusüss, 'Bin Gleich Zurück, (Be Right Back), 1984/87, Gelatin-silver print and wooden chair). Neususs' photogram uses the basics of photography (recording light on light-sensitive paper) in an incredibly direct way; a way that is somehow more direct, visceral, and indicates a respect for/ belief in/ reverence towards the aura of the individual. It is also akin to a mourning piece; who has left the chair? When will they be back? Where have they gone? The chair is a physical object, left behind almost as proof that the shadow recorded on the photosensitive paper came from a real person.

------------------------------------

Saw a play in the evening entitled "Black Watch" performed by the National Theatre of Scotland. And yes, they were from Scotland, possibly the sexiest country in the world if you close your eyes. (No offense Scotland, I simply mean that the Scottish accent is delectable. Like pie. A really good pie.) Surprisingly, the troupe broke into song several times, interpreting traditional Scottish folk

songs. Twa Recruitin' Sergeants in particular was completely intoxicating, with soaring harmonies and a haunting piano refrain trailing behind the vocals. Another example can be found here -- the song starts about 2'44" in. But I get ahead of myself. The play recounted the experiences of a group of soldiers from the Black Watch deployed to Afghanistan for their second tour. The setting sways back and forth from Afghanistan to a pub in Scotland several years later where the remaining men are being interviewed by a journalist trying to understand their experiences. It is an all male cast, and the only characters save the civilian journalist are Scottish soldiers. Through the unwinding of their experiences, it becomes obvious that the journalist's questions are naive, basic, and thoroughly inadequate. He is a surrogate for the public, struggling to make sense of the war. This was a touching, brutal, and inspired play. It was particularly revealing to see after attending War Horse, a very different kind of play that detailed a very different kind of war. One of the best scenes can be found on youtube - it has a wonderful folk song followed by a quick history of the Black Watch from the 1700's on.

------------------------------------

Also saw Damien Ortega's installation at the Barbican. It was a collection of sculptural works made in response to a news article chosen over the course of one month (September 2010, I believe). One reason I felt so drawn to this show was that each piece became a conversation with the artist- partially because we had access to the source material to which he was responding.

Fourth Plinth

Hello Blog,

It’s me, Celine. On Sunday we had class in the morning, followed by a visit to Trafalgar square to see the fourth plinth. We then went on to the ICA. Ended the evening with a dinner of bangers and mash at Whitehall with Iain and caught a showing of The King’s Speech with Emily.

Yinka Shonibare's Nelson's Ship in a Bottle is currently on the plinth. It is a recreation of the ship Nelson commanded in the battle of Trafalgar. This ship, however, has sails made of brightly colored and patterned fabric of the kind commonly found in West Africa. I've included a picture below I took several years ago in Benin that demonstrates an array of such fabrics. On the plaquard next to the plinth, Shonibare explains that this work "considers the birth of the British empire and multiculturalism in Britain today". This seems overly joyful and celebratory

compared to much of Shonibare's work, which consists of headless life-sized dummies shooting, raping, or dehumanizing other dummies (all clad in elaborate Victorian dress made from African fabrics). Like the rest of his oeuvre, a more complex, possibly sinister interpretation lies not far from the surface. The British empire profited hugely from the transatlantic slave trade, ferrying manufactured goods, captured men and women, and teas, coffee and spices in a triangle spanning three continents. This history is certainly embedded in the idea of multiculturalism. But there is also a confusing mix of cultures that has cropped up over the centuries; a confusion that is captured perfectly by Shonibare's use of the 'African' fabrics. While these fabrics have been sold the world over as African, their history is much more nuanced. Their origin lies in the woven patterns of African tribal ware. The patterns were reproduced in the west using batik (a fabric dying process) and over the years have been modernized; bright colors and complex, intense patterns are now commonplace, with unexpected images such as telephones showing up in the prints. Furthermore, the most expensive, highly regarded of these fabrics are produced in Holland, not in Africa. So what has come to be seen as a symbol of a cultural tradition is in fact a network of international relationships spanning several centuries.

--------------------------------------------

Emily has asked us to propose a piece for exhibition on the plinth. Prepare for genius.

I would propose a large, slumped bone, broken in two and tied back together with an anchor hitch. The entire piece would be made of cast rubber. I believe this proposal would touch on the physical toll of war, and would symbolize the role of war in nation building. I am also fascinated by the symbolic power of the knot in relation to the body; knotting a bone is not only absurd, it is ineffective, yet knotting is a form of repair commonly used to mend things in the external world.

Alternately, I would propose that a larger than life bronze cast of Nelson's missing arm be displayed horizontally on the plinth.

Westminster, Tate, Jurack

Hello Blog,

It’s me, Celine. On Friday we took a tour of Westminster Abbey, followed by a visit to the Tate Britain to see the Eadweard Muybridge show and Rachel Whiteread’s drawings. We ended the day with a talk from visiting artist Brigitte Jurack, who is German in nationality and teaches at Manchester University.

I was intrigued by Jurack's work.

At some point she began talking about the student protests, explaining the horrible injustice of her student's fees being tripled with one fell swoop with the help of the party that pledged to keep student fees consistant. She was genuinely upset, and seemed to be on the point of either crying or throwing something at points. She said that all this must be old hat for the Americans, and that maybe we weren't upset by the situation. I replied by saying that the American system was not going to change, and that if we were angry all the time we would be constantly depressed. Not my most eloquent moment. It elicited an outburst, and people started venting their frustration (most of which seemed aimed at me, oddly). By the end of the conversation, in which, predictably, nothing was accomplished or settled on, I was angry without really knowing why. But looking back, I think I was frustrated and upset with Brigitte. Well meaning though she was, she was despairing and lashing out against a system that she had never been subject to- she was speaking with fervor about students going into debt and how that would mar their futures for decades, as if trying to convince us that the system was broken. There is no need to tell me that I'm fucked. I know it. But what the hell else would you have us do? The British students are, even now, far far better off than their American counterparts. As for the student loan debt, I was insulted and angered that someone who had never had to live with the reality of student loans would be lecturing people who had consciously decided to take on debt to finance their future. Don't tell me that my life is going to be harder because of student loans, I know it will be, but again, what else am I supposed to do? I felt talked down to and almost scolded without knowing why. A depressing and disheartening way to end the day.

Serpentine, Saatchi, Globe

Hello Blog,

It’s me, Celine. On Thursday we went to the Serpentine Gallery, the Saatchi Gallery and had a tour of the Globe Theatre (a faithful reproduction of the theatre Shakepeare had built for his acting troupe). There were many crafty blobjects to be enjoyed by all (and yes, spellcheck, I mean blobjects, NOT ‘projects’). The highlight of the day was Phillippe Parreno’s exhibit at the Serpentine. It consisted of several choreographed videos that moved the audience through the Serpentine’s five four open rooms. Rather than playing on loop, the videos played in sequence, with the next video calling out as the previous video ended. The work spoke of loss; loss of reality, liberty, identity, and life. The most lyrical was titled June 8th, 1968. It was a simple five minute video shot from the point of view of those on board JFK's funeral train as it wound its way from Dallas to Washington DC in the days following his assasination. We the audience look out on beautiful windswept landscapes populated by various stony faced citizens who stare solemnly back at the camera, saying nothing. The only sounds are the train and the wind through the trees.

After each video, the curtains are raised. I was delighted to notice after the first video that it was snowing outside; the kind of lovely, gentle snow that one associates with childhood. As I came close to the floor length windows facing Kensington gardens, I noticed breath marks on the glass, at a child’s height, although there was no child in the room. It was only later that I realized both the snow and the breath marks were a part of the installation; the breath was actually etched onto the glass, while the snow was made of soap bubbles, timed to fall after the curtains rose.

Throughout the gallery there were also towers of plugs rising from the embedded outlets in the floor, plugs from all over the world, fitting male to female in a bizarre game of blocks, terminating in a plain orange night light. This collection of plug installations served to guide the gallery goers from room to room.

Saturday, January 8, 2011

The Tate and 'War Horse'

Hi, it's me, Celine. Wednesday, our group visited the Tate Modern. In the evening, we saw "War Horse" at the New London Theatre.

Our experience of the Tate was predictably dominated by the Ai Wei Wei piece entitled Sunflower Seeds. It is a mutable installation piece commissioned by the Tate, and consists of one hundred million handmade porcelain sunflower seeds covering a large rectangular portion of the vast turbine hall. At first glance, the piece is vastly understated; the porcelain seeds could be gravel taken from a parking lot. When I was close enough to the installation to see the hand painted ink stripes on each porcelain seed, an eerie sense of loos crept over me. Suddenly the silence of the space resonated like the dry air of a tomb. The work seemed static, dead. Strangely prophetic and accusatory; I felt sad and unaccountably uncomfortable.

The most successful and fascinating aspect of this work was its site specificity; it is the abstracted portrait of a town and a people who have lost their livlihood. Sunflower Seeds carries with it traces of its 1,600 makers. In other ways, I found the limitations of this piece severely disappointing. In the following youtube video, the originally intended interaction between viewer and work is demonstrated, as waves of people walk on the seeds.

There was also a place to record questions we had for Ai Weiwei, that were then uploaded to the Tate website. I asked if Ai if he personally thought that the act of making was inherently political, particularly in a culture where things could be purchased so easily. This question was fueled by thinking about the Craftivist movement, which makes that very claim. I'm currently working on a paper about Craftivism; I am very skeptical of several aspects of this movement. The video I recorded at the Tate can be found here:

I found a correlation between his work and that of Lisa Norton, who, in a series of work entitled Systems for Habitable Spaces, commissions craftspeople in China to carve mass-produced objects.

While contemplating this work, I found myself thinking about Craftivism. Sunflower Seeds took an entire town two years to complete; a tour de force of energy and craftsmanship. And the intention of the artist was undoubtedly bound up in socially responsible considerations-- could this work be seen as an example of successful Craftivism?

Questions I'm still mulling over:

-What is the significance of the number of seeds?

-What is the political nature of the work?

-Do you believe that the act of making is inherently political?

-Could a relationship be drawn between your work and the British born 'slow movement'?

-How do you feel about the representation of Chinese citizens as sunflower seeds?

-Why did you want your audience to walk on the seeds? Why not choose another form of interaction that did not involve having the seeds on the floor?

-Why did you choose to emphasize the sunflower seeds' collective surface area rather than their weight or volume?

-Sunflower seeds can be seen as an ambiguous symbol- either emblamatic of potential growth or the shell of spent possibilities. What larger metaphoric meanings were you considering when using this Maoist symbol?

-Place vs. Displacement = your work seems very concerned with the particularities of place, using symbols materials and methods of making that are specific (and perhaps unique) to the community in which they were made. What do you want this work to gain by its displacement to another country?

-How much control was it necessary to reliquish in the direction and completion of this massive project? Did you see it as a collaboration? What did loss of control add to the work?

Tuesday, January 4, 2011

Turner Prize

Dear Blog,

It's me, Celine. Yesterday we went to the 2010 Turner prize exhibition at the British Museum. The finalists were Dexter Dalwood (painter), The Otolith Group (video), Angela De La Cruz (painter/sculptor), and Susan Philipsz (sound installation). I'll say upfront that I couldn't stay awake for the Otolith Group's 45 minute video-- after a red-eye flight to London, the dark lights and soft audio were lulling me to sleep. I only lasted about 15 minutes, not enough to properly judge their exhibit.

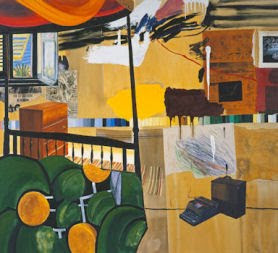

Dezter Dalwood's paintings were interesting-- he painted in a style that consciously affected the style of collage, creating depth and then contradicting his efforts with flat, bold expanses of paint that look as if they came from a magazine (or a Russian propoganda leaflet).

Dexter Dalwood, Greenham Common, 2008.

Each painting is a pastiche; not only of artwork found in most art history textbooks, but of important, albeit obscure, moments in history. Greenham Common, in its setting, seems to reference Manet's Dejeuner Sur L'herbe. The white expanse bounded by a gestural line seen in the lower left seems to suggest a drooping arm- the most direct reference to the absence of human subjects in the body of work presented at the Tate. The work's title, Greenham Common, was the name of a defunct U.S. military airfield located in England, opened in the 1930's and closed at the end of the cold war. Dalwood's paintings are highly symbolic, and draw on the rich history of painting to provide abstracted portraits of specific people and places.

Dexter Dalwood, Borroughs in Tangiers, 2005

Although his painting has the bold brushwork and bright color scheme associated with early abstract painting (think fauvism and surrealism) he is committed to drawing deeply from the well of history in the creation of the above domestic scene. Despite the painting's modest size (about 3'x3') Dalwood has managed to cram over five hundred years of art history into it's frame. In the upper left corner, Botticelli's Birth of Venus is shown hanging on the bedroom wall. Around it, the characteristic scribbling and stabbing strokes of Cy Twombly festoon the walls, with a bedspread whose patterning is reminiscent of Gaugin's work. We, the viewers, peer into this scene as if we have just opened a door onto a bedroom that has been violently, even haphazzardly decorated-by a subject who is nowhere to be found.

Angela De La Cruz's wall tag described her work as "sculpture that speaks the language of painting". I found this an apt description, if ultimately falling short of the work's force. De La Cruz paints canvases with slick, bright colors reminiscent of road signs, and mounts them on fractured frames. The effect of such an action is an deflated painting that curiously undermines the medium of which it speaks. In some cases, the canvases are peeling away from their frames, detaching themselves from the history that gives them authority. In others, they flop limply like a dying animal, held upright by steel brackets that act as prosthetic devices. While one could easily criticize the timliness of this work (De La Cruz's work bears a striking similarity to Robert Morris' limp, rectangular sections of industrial felt, first exhibited in the late 196os) it is De La Cruz's remarkable attention to detail and subtle additions to her historical precedents that make this work so poignant. Like Dalwood, she is fully aware of painting's history, and makes reference to this knowledge in her work. Unlike Dalwood, De La Cruz simultaneously undermines and supports her medium in a deliciously tongue-in-cheek commentary on the state of contemporary art. A feminist interpretation of this work provides further fruitful territory; De La Cruz engages in the emasculation of painting- violently breaking the frame and allowing the fabric to flow freely, draping, sagging, and taking on sculptural form. She frees her colorfield paintings from their constraints, simultaneously denying the frame's function and accepting the materiality of the frame as a sculptural element.

Angela De La Cruz, Clutter XXL, 2008

Angela De La Cruz, Clutter I, 2003

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)